This article was written on May 28, 2016 by Greg Seiter and originally appeared in a special insert published by the Daily Journal

Calvin Higgens, Marine

- Birthplace/Hometown: Indianapolis

- Residence: Indianapolis

- Years of service: 1944-46

- Branch of service: U.S. Marines

- Assigned unit: 3rd Platoon, K Co., 22nd Marine Regiment, 6th Marine Div. (Okinawa, Japan)

- Duties: Rifleman

- Rank Attained: PSE

He didn't want to be seen as a slacker

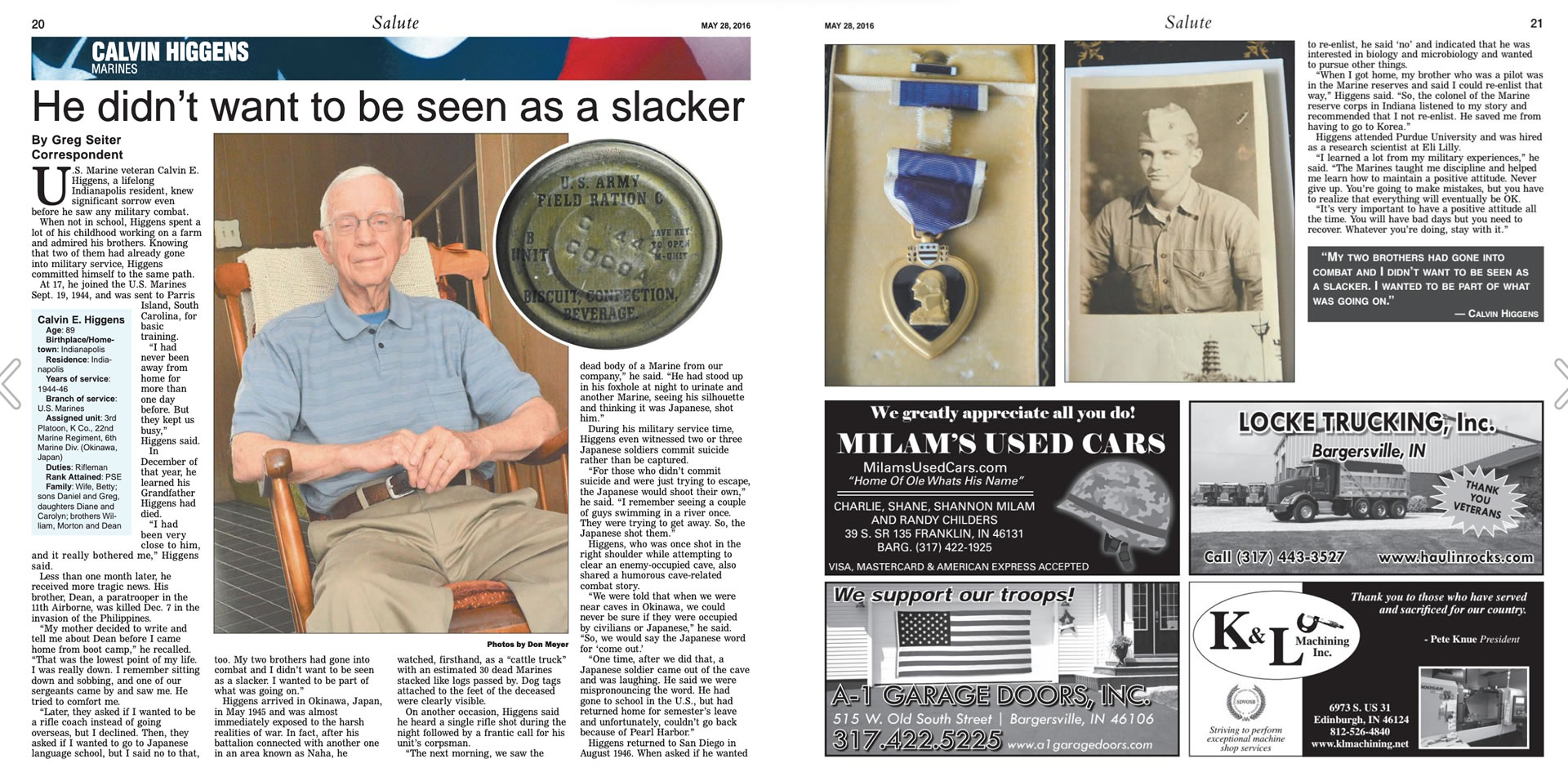

U. S. Marine veteran Calvin E. Higgens, a lifelong Indianapolis resident, knew significant sorrow even before he saw any military combat. When not in school, Higgens spent a lot of his childhood working on a farm and admired his brothers. Knowing that two of them had already gone into military service, Higgens committed himself to the same path.

At 17, he joined the U.S. Marines Sept. 19, 1944, and was sent to Parris Island, South Carolina, for basic training.

“I had never been away from home for more than one day before. But they kept us busy,” Higgens said.

In December of that year, he learned his Grandfather Higgens had died.

“I had been very close to him, and it really bothered me,” Higgens said.

Less than one month later, he received more tragic news. His brother, Dean, a paratrooper in the nth Airborne, was killed Dec. 7 in the invasion of the Philippines.

“My mother decided to write and tell me about Dean before I came home from boot camp,” he recalled. “That was the lowest point of my life. I was really down. I remember sitting down and sobbing, and one of our sergeants came by and saw me. He tried to comfort me.”

“Later, they asked if I wanted to be a rifle coach instead of going overseas, but I declined. Then, they asked if I wanted to go to Japanese language school, but I said no to that, too. My two brothers had gone into combat and I didn’t want to be seen as a slacker. I wanted to be part of what was going on.”

Higgens arrived in Okinawa, Japan, in May 1945 and was almost immediately exposed to the harsh realities of war. In fact, after his battalion connected with another one in an area known as Naha, he watched, firsthand, as a “cattle truck” with an estimated 30 dead Marines stacked like logs passed by. Dog tags attached to the feet of the deceased were clearly visible.

On another occasion, Higgens said he heard a single rifle shot during the night followed by a frantic call for his unit’s corpsman.

“The next morning, we saw the dead body of a Marine from our company,” he said. “He had stood up in his foxhole at night to urinate and another Marine, seeing his silhouette and thinking it was Japanese, shot him.”

During his military service time, Higgens even witnessed two or three Japanese soldiers commit suicide rather than be captured.

“For those who didn’t commit suicide and were just trying to escape, the Japanese would shoot their own,” he said. “I remember seeing a couple of guys swimming in a river once. They were trying to get away. So, the Japanese shot them.”

Higgens, who was once shot in the right shoulder while attempting to clear an enemy-occupied cave, also shared a humorous cave-related combat story.

“We were told that when we were near caves in Okinawa, we could never be sure if they were occupied by civilians or Japanese,” he said.

“So, we would say the Japanese word for ‘come out.’

“One time, after we did that, a Japanese soldier came out of the cave and was laughing. He said we were mispronouncing the word. He had gone to school in the U.S. , but had returned home for semester’s leave and unfortunately, couldn’t go back because of Pearl Harbor.”

Higgens returned to San Diego in August 1946. When asked if he wanted to re-enlist, he said ‘no’ and indicated that he was interested in biology and microbiology and wanted to pursue other things.

“When I got home, my brother who was a pilot was in the Marine reserves and said I could re-enlist that way,” Higgens said. “So, the colonel of the Marine reserve corps in Indiana listened to my story and recommended that I not re-enlist. He saved me from having to go to Korea.

Higgens attended Purdue University and was hired as a research scientist at Eli Lilly.

“I learned a lot from my military experiences,” he said. “The Marines taught me discipline and helped me learn how to maintain a positive attitude. Never give up. You’re going to make mistakes, but you have to realize that everything will eventually be OK “

“It’s very important to have a positive attitude all the time. You will have bad days but you need to recover. Whatever you’re doing, stay with it.”

Original Article Scan: